April 2024 Subscription with Natividad Benitez and Darabiel Osorio

A mineral smell of wet soil kicks up into the dewy air and occasional wild glassy pink raspberries blur past as our sweet stubborn truck insists its taken this trip hundreds of times, with hundreds more to come. The navy 90's toyota pickup tires defiantly slipping and gaining traction in the morning mud, as we climb to the top of a plateau near the summit of El Cielito village in Santa Barbara.

Benjamin and I are driving further up through Las Flores neighbourhood to see a very important person (Natividad Benitez) in neighbouring Cielito. Nati helped introduce the idea to the community that growing coffee for the specialty market could work through his winning of the 2nd annual Cup of Excellence competition. Incidentally, I was there on that trip as part of the international jury for the same competition.

This was back in 2013, just before my first coffee buying job was to start, unaware that this visit was the start of a decade-long (and counting) friendship with Peña Blanca born and raised Benjamin, and a sincere love and respect for the coffee growing scene in Santa Barbara, Honduras at large. As we drive, we pass farms, many no larger than a hectare or two - each one Benjamin points out the producers' name but also the roaster who buys their coffee. He does this dozens of times over that first visit and years later, when I last visited in 2016, I was nearly able to do the same.

Here's a little context from a roaster's perspective because I think it's important to share it - From in the late 2000's and through the early to mid 2010's, you were hardly considered a specialty coffee roaster if coffees from Santa Bárbara didn't find it onto your menu. In the cupping lab perched on top of the offices, a glass window looking down to the concrete slab dry mill at Beneficio San Vicente, you could find coffee bags on the backbench beside the grinder, like a kind of 'all stars' sports team, a sign that this cupping lab gets a mind numbing amount of visitors. From roasters like France's Belleville, Norway's Tim Wendelboe, Australia's seven seeds, SF's Ritual and countless more, each of these bags represent multi year commitments. No multi year contracts or anything like that - Just a mutual goal to be there and do this for the longterm. In the vast majority of cases, everyone comes here to visit the producers they work with, and cup if it's the time of year when harvest is happening. This is a stark contrast to what normally happens in cupping labs where folks come through with the intention of picking the best and leaving the rest. That wasn't the culture Benjamin and his cousin Arturo built. The culture was far more supportive and productive as a result.

Those years of facilitation were incredibly effective. Benjamin has been a key part of developing a network of producers and roasters, the idea being to build an increasing resilient culture of roasters buying from the same producers each year, and when a producer has more yield than expected, there are others who are interested in buying the remainder if a roaster isn't big enough to take the whole production. Benjamin says, "a lot of producers now know exactly where their coffees are going, and they’re proud to be producing them."

With the successes, there are sizeable challenges, however. There are migration and labor crises, erratic weather, hurricanes, resulting in fewer people to help and higher costs to produce. In an increasingly hyper competitive industry, its also true that not everyone sees the value of clean washed coffees, at the prices they need to command. But at the same time there are producers who've' invested in their farms, who trust coffee drinkers to understand the value of the human labor that goes into it.

We plant things because we hope. There's hope in our reaching.

Connectivity and agency

In Vancouver, tucked into a semi public garden art space on Union street in Strathcona, there's a node installed acting as the first step in an open community network. This project is called Stolon Mesh. Stolons, also known as runners, are horizontal connections between parts of an organism. They may be part of the organism, or of its skeleton. Think of something like a strawberry plant and how that grows.

From 221a.ca

“ MESH networks offer a way for a community to own and run a Wi-Fi network. Store-bought hardware and open-source software are all that’s required to launch a MESH. Typical use cases for MESH networks include providing an alternative to corporate ISPs, as a way to run internet in areas that lack this service, or in temporary, emergency situations. The simplest MESH starts with a Wi-Fi router placed at a high vantage point—on the roof of a house or building—connecting to one or more additional routers.1 Such a setup has only limited capacity, however; streaming services like Netflix would be out of the question for users of a simple MESH. Instead, extensive, well-functioning MESH networks use an ISP-like hub and spoke system for strong, reliable data transmission.”

Vancouver's 'Stolon Mesh' is modest at two nodes, the second one placed on top of the Artiste building on Great Northern Way. But it represents a planting of something. A reaching for each other in order to build a resilient network of computers, sure, but ultimately of people.

If this interests you, there are far larger and mature mesh projects in areas like Brooklyn, who were able to connect directly to fibre optic links, effectively replacing a traditional ISP.

The most impressive is guifi.net in the Catalan region of Spain, with their mesh network boasting nearly 38k nodes. These networks exist to some degree in Seattle, Portland, Toronto, Detroit and countless other places.

We plant things because we hope. We reach out because we trust someone will meet our reaching.

Community mesh

When thinking about the Santa Barbara community, I hold both what the folks in Santa Barbara are doing, and community mesh networks in my mind, and clearly see the similarities. Mutual prosperity, support and access for all. The more buy in, the more resilient the network becomes.

There's another network of sorts that coffee plants use - In a previous zine we talk about the wood wide web, and the clear ways that fungi facilitate nutrient uptake in plants, including coffee. There seems to be increasing consensus that taking things away in the form of applying fungicides and pesticides, as well as applying NPK synthetic fertilizer is cutting off coffee plants from its support network in countless ways, some ways we're aware of, and plenty more that we're not.

The second coffee in your box this month is courtesy of Darabiel Osorio and his unbridled enthusiasm for regenerative and microbe friendly farming. In his farm in Tarqui. Huila, Colombia, Darabiel makes things like supermagro (you can search on youtube if you want to give it a go for those who are lucky to have a garden), referred to as a 'full spectrum bio fertilizer'. The antithesis to fungicides.

Sometimes all of this seems saccharine, its easy to devolve to nihilism with so many examples of things that aren't working in coffee - but there's an art to moving forward together - To support the things that are working, even when it isn't perfect or in its final form yet.

In your box this month

When this small lot from Natividad became available, Benjamin texted me about it and asked if we wanted to buy it back in the fall - I'd be lying if I said I wasn't waiting six years to be asked. To be able to share coffee from the person who kicked off entire movement into specialty coffee, the first node on the highest vantage point, is literally offering a slice of history and context to you is so rad.

Natividad, along with the rest of the Santa Barbara community building a resilient producer/ buyer network, as well as Darabiel's focus on regenerative ag concepts, are both examples of practices we want to see in the world. So we buy their coffee. And in turn you've supported their work too.

Enjoy both and see ya next month

Natividad Benitez

When thinking about top coffees from, Santa Bárbara is first on many people's minds. It's almost not believable that this wasn't always the case.

Back in the 90's, the closest dry mill (Beneficio San Vicente or BSV) regularly received wet parchment coffee from various families, and due to the state it was received in, not picked ripe or processed well at all (often not dried), its fate was to be sold in the local market all blended and dried in towering mechanical driers. Drying your own parchment as a producer wasn't really done at that time.

It wasn't until 2004, when Benjamin and Arturo of San Vicente mill in Peña Blanca made a decision that would create a paradigm shift for the whole region. They bought a delivery from Natividad Benitez, cupped it, then entered it into 2005's Honduras 2nd annual cup of excellence competition. Before this, Don Nati wasn't producing specialty and only a tiny portion of his land was devoted to coffee. I'm honestly not sure if Natividad knew about his coffee being entered initially - I don't think he did! If you've not heard of Cup of Excellence, it's a coffee competition for producers in various countries. Farmers will pick their top lot to be evaluated by an in-country jury, then an international group of cuppers. This process ends with each coffee ranked and an auction where coffees can reach life-changing prices. Producers essentially become famous amongst roasters and green buyers.

The day when Natividad's lot took an astonishing 1st place marked a shift for the people of Santa Bárbara - That moment kicked off a new reputation as coffee producers that rival the worlds brightest. People felt supported in their work over the subsequent years, and the shift in the community (financially especially) was palpable. A huge part of why this worked so well is because Benjamin is an incredible facilitator. He's got help now thankfully, but initially the 280-some producers were all swirling in his head somehow, and roasters through the 2010's until today have been able to develop stable buying relationships that last, in large part thanks to Benjamin's tireless efforts. I'm sure I can speak for many in the coffee industry when I say I consider him among my dearest friends.

Fast forward years later - Routinely, coffees from Santa Bárbara place in the top 10 and often win. Almost poetically, nearly 20 years after that first Santa Bárbara entry, Benjamin Paz earned the top spot in the 2022 iteration of COE Honduras.

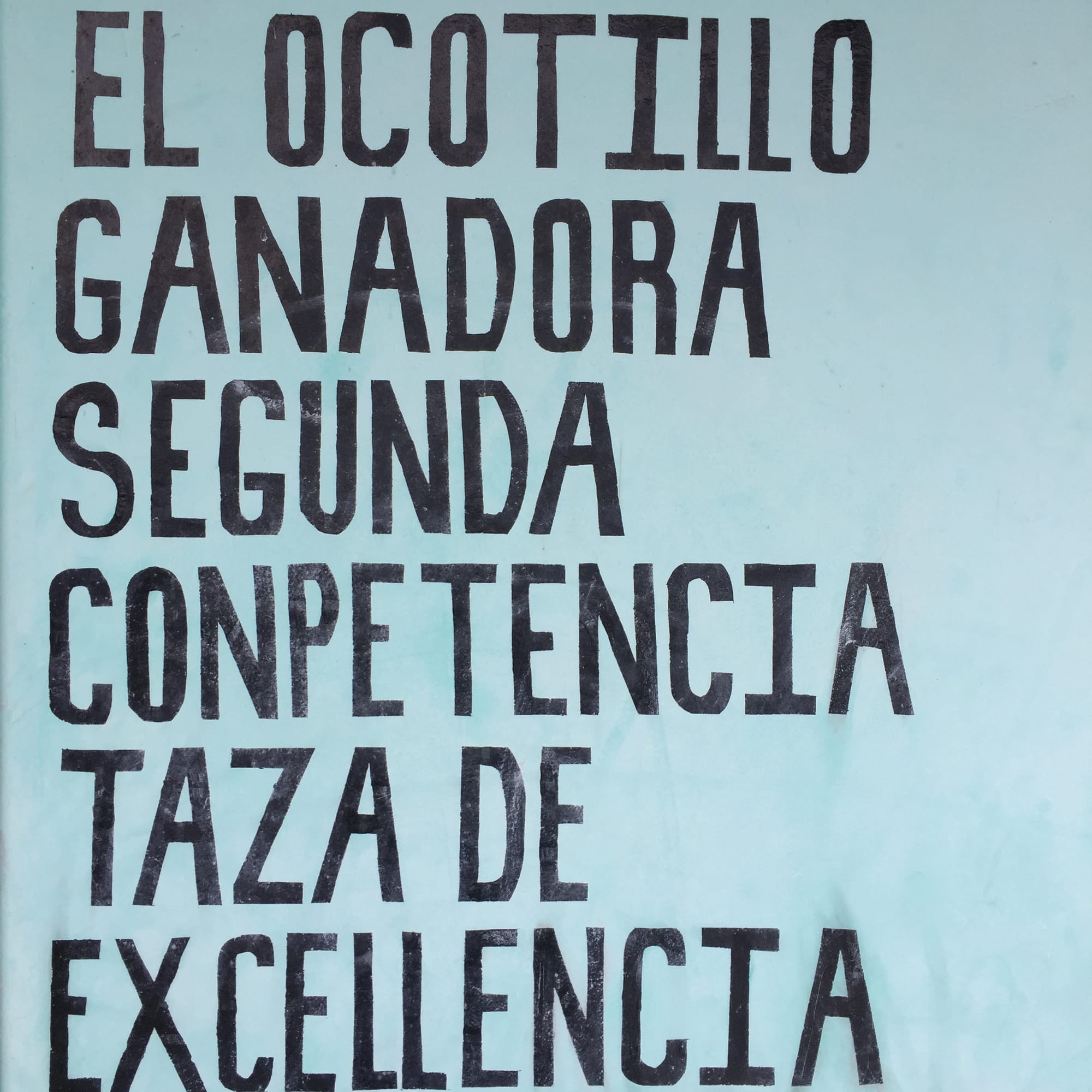

This is 3x69kg bag mini Pacas lot from Natividad and his wife Vilma from their farm in Cielito called El Ocotillo - I've known them over my last decade in coffee and its incredibly sentimental to me to be able to share their coffee with you.

Darabiel Osorio

Caturra and variedad Colombia from Darabiel’s 1.5 ha farm Finca Prigamosas at 1800 masl in El Líbano, outside of Tarqui, Huila.

Darabiel has been a long-time practitioner of ecologically guided agriculture. He has a great water filtration system that uses bacteria and organic waste to remove nitrogen and phosphorus from the filtered water. He has been making fermented brews- like Super Magro- on his farm, which has led to a reduction in roya and healthier plants. He has reduced his chemical fertilizer applications by half, and he’s even trading the fermented brew preparations for his neighbours’ coffee pulp to increase his organic compost and return more organic material to his soils. The name of his farm- Finca Pringamosas- is named for nettles that make up ground cover on his farm.

Darabiel floats cherries before de-pulping them to remove over- and under-ripe cherries, to make a more even substrate for fermentation. From there, he de-pulps the coffee into a sealed plastic pickle barrel, where the coffee ferments in a low-oxygen environment for around 48 hours. From there, he takes it to his dryer (first a pre-dry in a cool, tin-roofed dryer, and then it finishes in a shaded but warmer dryer higher on the hill with more wind). Drying takes between 15 and 25 days.

Luna is powered by Laura & Nate, two industry nerds from Vancouver, Canada. What you just read comes as a printed colour zine each month, alongside two coffees specifically sourced for subscribers. Join us next time!