How to guide: Make a hybrid

If you’ve been with us for awhile, you can likely rattle off a few hybrid varieties (Castillo, Colombia or Ruiru 11 anyone?) and you possibly appreciate their ability to be more resilient in the face of climate change while still tasting great. How do hybrids actually become hybrids though? Is there any GMO meddling involved? Absolutely not. Does it take awhile? You bet. Here’s a handy how-to guide using Parainema as an example.

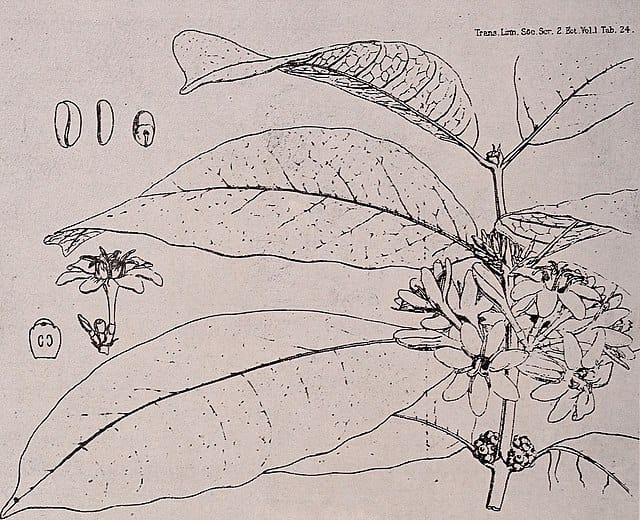

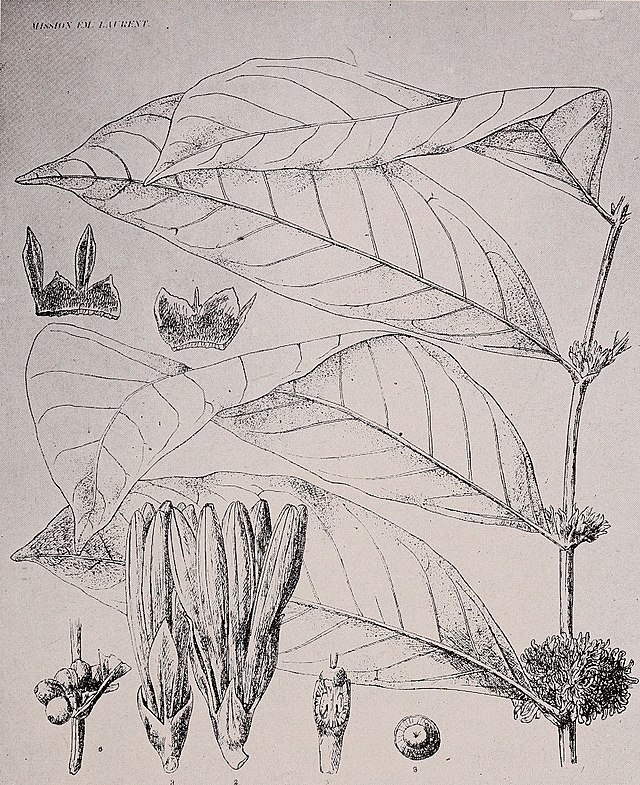

In 1958/1959, the Centro de Investigação das Ferrugens do Cafeeiro of Portugal (CIFC), famous for its research into coffee leaf rust, received a bunch of Timor Hybrid seeds from the island of Timor. Timor Hybrid is a natural cross between C. arabica and C. canephora (Robusta) that appeared spontaneously on the island of Timor in the 1920s. Its Robusta genetics granted rust resistance into the variety.

Step 1: Aquire some seeds with a helpful trait.

In 1958/1959, the Centro de Investigação das Ferrugens do Cafeeiro of Portugal (CIFC), famous for its research into coffee leaf rust, received a bunch of Timor Hybrid seeds from the island of Timor. Timor Hybrid is a natural cross between C. arabica and C. canephora (Robusta) that appeared spontaneously on the island of Timor in the 1920s. Its Robusta genetics granted rust resistance into the variety.

Step 2: Select the most promising specimens.

From the two shipments of seeds that CIFC received, they had selected two of what they thought were the most resilient plants for use in breeding based on their high resistance to leaf rust.

Step 3: Choose a complementary variety to cross-pollinate by hand.

In 1967, breeders in Portugal began work to create new varieties of coffee that would be resistant to leaf rust, but also have a compact stature that could be planted more densely. One of the rust-resistant Timor Hybrid plants, called HDT CIFC 832/2 (memorable, I know), was crossed with the compact Villa Sarchi (a natural Bourbon mutation) to create hybrid 361 (H361). Cross-pollination involves a paintbrush and literally going to flowers on one variety and painting them onto the different variety. It’s a manual and painstaking process.

Step 4: Give the resulting babies a snazzy new name.

This hybrid was dubbed “Sarchimor.”

Step 5: Send the most promising babies out into the field

Fortuitously, they created this new hybrid just in time for the arrival of leaf rust in the Americas in the 70s.

After some initial testing at IAC in Brazil, in 1971 CIFC sent H361 out for field trials in experimental centers in many countries, including Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, the Dominican Republic, Laos, Malawi, Mozambique, Sao Tome, Thailand and Venezuela. In response to the leaf rust crisis, Central American countries banded together to form the Regional Cooperative Program for the Technological Development and Modernization of the Coffee Industry (PROMECAFE) in 1978.

Step 6: Grow & strengthen the family tree

Selections of the babies are further studied and naturalized into their new environments.

In Central America, H361 was first sent to the Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (CATIE) research station in Costa Rica. The population studied there was given the designation T5296 (“T” represents the Turrialba, the town where CATIE is based). The work of selective breeding on T5296 was led by researcher AJ Bettencourt. From this central trial, T5296 was sent out to national breeding programs in the region.

Step 7: Time goes by…Multiple generations and decades of Sarchimor selections later, Parainema is launched in Honduras from T5296

In Honduras, further generations of selection led to the variety that is known as Parainema. In El Salvador, further generations of selection led to the variety that is known as Cuscatleco. In Puerto Rico, the Sarchimor population was called Limani.

Similar selections were done in Brazil to create Obata, Tupi, and IAPAR 59.

On Rotation – Kiwi Cola, Parainema by Hildaly Leiva

What’s it like starting a farm & interacting with a new variety?

“My dad was a coffee producer, so I grew up watching how a farm was managed. I learned a lot about how to manage a farm and I assisted doing a lot of things, from picking cherries to planting nursery plants. 10 years ago, I had the opportunity to buy my own land to plant coffee (I did not know anything about special coffee at the time), a relative of mine gave me a Catuai seed and I made the nursery and I planted it, but this farm did not last me long since in 2011 a strong outbreak of a disease came across the country that we did not know, rust. Then a neighbour offered me seed of a new variety that was of good quality and had won cup of excellence in 2015 (Eulogio Martínez was the first in the area to have Parainema coffee); So I planted almost the entire farm with Parainema and 2 years later a friend helped me take a sample of my coffee to the laboratory of the Exportadora San Vicente and there they helped me offer it to buyers and since then I have a better market for coffee from my farm.”Hildaly Leiva, Parainema producer in Santa Barbara, Honduras

*It’s important to note that, Sarchimor is not itself a distinct variety. Instead, it is a group of many different distinct varieties with similar parentage. Despite all this work over decades, T5296 is technically still not as stable as heirloom varieties and may never be, however, the ability to thrive and produce well for farmers navigating climate change makes this hybrid essential.