January 2025 Subscription - 'Nouveau Terroir'

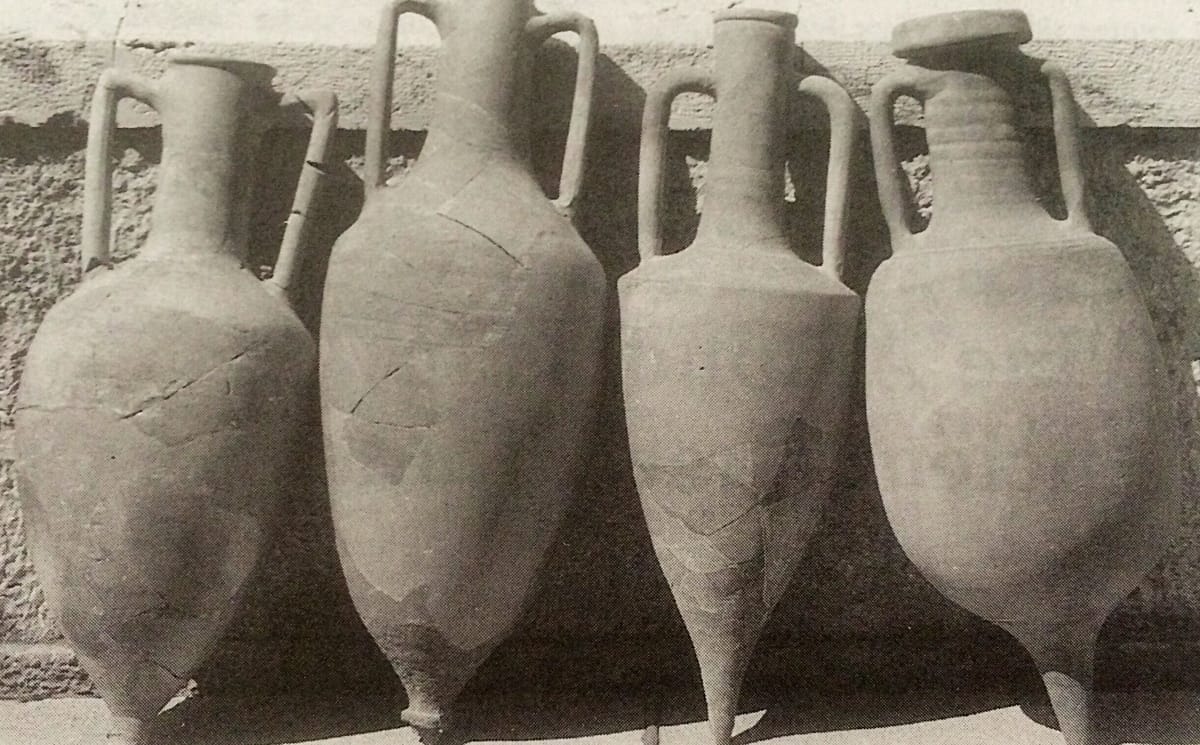

Clay amphora called qvevri, thick oblong vessels that look to you like they would be right at home on the set of the Fifth Element's opening scene, suspended in steel frames (often, these are buried into the floor of a wine makers facility). From here, you're told the grapes are left with the skins floating on top for 10 months (or as much as a couple years), with the local yeasts and microbes cocooned under the beeswax sealed lid, the egg shaped clay almost gestating.

Looking at the qvevri lined up, each a womb to a living ferment, it feels like a trip to the Caucasus country of Georgia, the origin of this method of wine making (and perhaps, the origin of winemaking entirely). But outside the doors are rolling hills of wild sage and desert things, cool nights and diurnal shifts to warm days. It's the landscape of a wine farm started by friends in 2018 in the Similkameen Valley, B.C. called Scout. It’s not tradition, not here anyway, but it is somewhere, and it’s made into a new thing in this place. You roll with it.

Terroir is a word said in many food and drink realms, almost flippantly as if there's a single definition. This word isn't so universally understood though. The original meaning came from France to simply mean the territory of a village (13th century) and shifted to inextricably link the term with the soil (17th century).

Today, UNESCO gives this definition: “a geographical limited area where a human community generates and accumulates along its history a set of cultural distinctive features, knowledges and practices based on a system of interactions between biophysical and human factors. The combination of techniques involved in production reveals originality, confers typicity and leads to a reputation for goods originating from this geographical area, and therefore for its inhabitants. The terroirs are living and innovating spaces that cannot be reduced only to tradition”.

The UNESCO definition has its wrinkles (though it's pretty good), and when turning to the coffee industry, namely, the opinions offered by various roasters, importers, and coffee heads over the years, we run into some issues as well.

A Wrinkle in Time

Terroir is often seen as rigid and the term carries a lot of baggage. It can lead to protectionist tendencies that (unintentionally) extract the maker from her subject (producing coffee) in pursuit of a coffee that should have a specific flavour profile dependant on origin country or region. But with a changing climate, and the incredible speed of changing palettes and ideas of what a 'top coffee' should taste like, this puts producers in the centre of a tug of war.

The first idea, one that you might hear in coffee documentaries in the 2010's, and certainly the one I grew up in the coffee industry hearing, is that coffee should be as close to the fruit on the branch as possible. Our job as growers, roasters and brewers alike, is to preserve the fruit and to simply not mess it up. That's a foundational perspective that the first waves of specialty coffee was built on. It's what distinguished special coffees from commodity ones and it was brimming with good intentions. For awhile, this idea held, and many roasters were linking up with producers and buying from the same producers each harvest cycle and that seemed to be working somewhat.

In 2013, in my first days as a green buyer for a larger roaster on the west coast, in my first week on the job, I saw the writing on the wall, however. We'd just received a container bound for a flagship espresso blend, and the first test batches were roasted. The assistant roaster tapped me on the shoulder to produce a plastic sample tray of the aforementioned coffee, absolutely riddled with quakers.

2013 was the year an unprecedented leaf rust (roya) outbreak tore through Central America. It's spread was among the most devastating in history. From as early as 1860 in Sri Lanka, to 1970 in Brazil, the 1980s in Colombia and Central America in the 2010s, leaf rust H. Vastatrix found its way to most of the coffee growing regions. This pathogenic fungus loves warm wet conditions, it feeds on the nutrition in coffee plants, causing leaves to fall off leaving orange dusty spores in its wake. It results in a lack of fruit maturation, leaving fruit underdeveloped, and a general loss in both quality an quantity of production. The very tangible way I found out about this was in that sample tray passed to me that day in June. It meant massive curve balls for roasters, and significant (sometimes life or death) financial challenges for producers with lower yields and lots full of defects, and often, not super sympathetic or understanding customers on the other end.

From those first days in the hot seat working for a larger roaster, to today, I've witnessed so many pivots.

One of them was leaning into new hardier varieties like the hybrid Parainema (which is coming back later this winter by the way!) which came to fame in 2015 in Honduras, and others like Castillo from Colombia.

Another, which has come more recently, is something that Jhoan Vergara (in your box this month) has been at the forefront of - Taking and culturing yeasts on different parts of his family fam Las Flores, getting to know what they do in fermentation, noting the resulting flavours through cupping, and taking a more direct approach with it all.

The 'Nouveau Terroir'

Heady jasmine, fruit loops, mixed tropical fruits, juniper & fresh pine tips though the finish - It's a pacific northwest/ tropical rainforest mashup with an unserious kids cereal note. Jhoan understands how to wield alchemy in coffee processing. He started as a kid, and he's not stopping any time soon. His coffees have an undeniable signature profile that he has somehow hit consistently - I can't stress enough to you how hard that is to do.

This isn't a co-ferment with fruit added to aide in the process, but rather, taking and concentrating cultures and working with what he's got to transform his coffees into something that expresses place and time in a poetic way.

Speaking off the cuff here, I also think Jhoan has sharp intuition.

I keep thinking about an article I read last year about how Camembert and Brie cheeses are both hanging by a fungal thread, and may be in danger of disappearing completely. P. camemberti, a strain of fungi became the inoculant of choice for these cheeses the world over for the last hundred years, loved for the fluffy albino rind it produced. There were plenty of other strains of fungi in use before this one but today, all Brie and Camembert is made using this one strain. The issue cheesemakers and scientists have run into is this strain can't reproduce sexually, like most other strains can - So we've been cloning this strain in order to continue cultivating it for the production of these cheeses. More recently, its getting more and more difficult to successfully even clone this strain. The theory is, as clones are generated from the same specimen over decades, you have the increasing potential to introduce harmful errors into its genome. Folks who are working on this think that's why it's becoming difficult to make copies of this strain.

It makes me wonder what's happening in the microbial world in coffee? We do know that specific microbes like to be at certain temperatures, and the coffee industry's fixation with altitude was really about the microbes who couldn't care less that it's above 2000masl, but rather that it's at a comfy temp for them. What does this mean when the temperatures warm or start to become erratic? I think we're already finding out.

What Jhoan's doing is really special because it's not co-ferments with fruits, it's not clinical commercial yeasts (nothing wrong with using those by the way), it's a third thing. It's celebrating the diversity of what's going on already on the farm, turning the different yeast cultures into a mixing board, except instead of sounds, it's a specific confluence of microbes that result in specific flavours. Jhoan could also be thinking about this preservation of cultures with climate change in mind, but I'll have to ask him.

I think there's an argument in there that Jhoan's take on processing is perhaps even more in the spirit of honouring terroir than just 'letting it happen'. Certainly it's more interesting. It's terroir as tending to a living changing thing, rather than doing what's always been done.

Jhoan is practising coffee growing and processing as craft. This is getting much closer to the UNESCO definition, and in my mind, further from the one I was told when I first got into coffee. It's in the choices and results from humans and microbes across time, temperature and vessel (whether it be in qvevri with wine or glass or ceramic tank with coffee) where the idea of terroir lives. But this doesn't happen in a vacuum, there also needs be a community.

At every pivot across the last couple decades, producers needed buy in from buyers (ofc) , roasters, cafes and home brewers. They needed to know that if they tried something new to be able to stay afloat as farmers, would there be support?

This rigid thinking of locking in what a Caturra or a Bourbon or a Maragogype should taste like in Colombia, Brasil or Nicaragua ties producers hands, eschewing progress and survival of a farm longterm in the name of "preserving terroir". This rigid thinking lacks empathy. It resists the reality of a changing climate. Its a slippery slope where coffee quality is declining but we turn our noses up at the very things that would put producers back in the drivers seat for quality (like what Jhoan's doing).

The pushback of this argument has validity though - Some producers lucky enough to be well connected to someone who knows about new processing techniques or producers affluent enough to hire consulting, those folks will likely be more than ok. It's the folks that don't have the right connections or information, and are asking buyers who likely don't have the kind of pragmatic grasp on processing that you'd have to possess in order to pass on complete information - That's where the bulk of issues are. This is something that Jhoan Vergara and Nestor Lasso along with their families are working to resolve in their community by building a community processing facility. The idea of banding together and making the space for free flow of ideas is something the Guacharos group is no stranger to (Nestor's father Jose Uribe Lasso is part of this group as well as Ildefonso Cordoba, also in your box this month). Over the years, it's together that this community of producers has leaned on each other, shared and experimented with different processing methods, shared group access to agronomists and other professional assistance, to make it a coffee growing group that, if enough time goes by, deserves a tip of the hat by UNESCO.

It's a Pink Bourbon party in your box this month, with Jhoan's and Ildefonso Cordoba's take (with a more banana guava thing going on). Both delightful encapsulations of their respective crafts. Both bringing that sometimes nebulous definition of 'what's terroir anyway?' more into focus.

Enjoy both and hope you have a great start to 2025!

Laura & Nate

Links and further reading

More on Ildefonso, Guacharos group and Pink Bourbon https://journal.enjoylunacoffee.com/seed-sharing-and-the-enigmatic-history-of-pink-bourbon/

Camembert dissappearing act

https://www.vox.com/down-to-earth/2024/2/10/24065277/cheese-extinction-camembert-brie-mold

Lucia Solis' Making Coffee Podcast Episodes on Terroir (here's one of them) - Lucia's episodes unpacking terroir as it relates to coffee inspired us to think about what terroir means for us, and to look at how the different producers we work are thinking about it.

Luna is powered by Laura & Nate, two industry nerds from Vancouver, Canada. What you just read comes as a printed colour zine each month, alongside two coffees specifically sourced for subscribers. Join us next time!