The Lifecycle of green coffee and what we do around here to roll with it.

*from our archive, originally published in our newsletter September 2020

Nate and I have been talking to each other a lot about green coffee (because of course, that’s what happens when your entire household is coffee focused).

Often we’re both thinking many months into the future when we nail down what we want to bring in for you – and a huge part of that is predicting how that coffee is going to hold up on the menu through the time it takes to travel to us, and through the time we’re roasting it.

But isn’t coffee shelf stable?

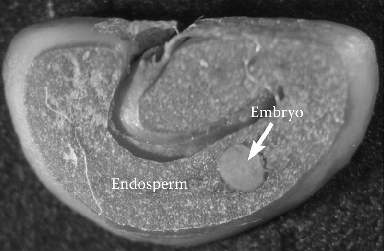

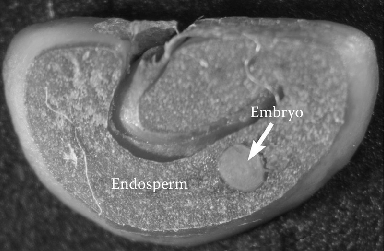

It is, yes, but if you look at a cross-section of a coffee seed, you’ll see something that is pretty familiar if you’ve ever sprouted anything (fellow kitchen hippies, hi). After coffee is roasted, of course, it can’t germinate. Here’s the thing though, when a coffee seed isn’t roasted it can – and should – be able to sprout under the right conditions.

So, for us, if we’re tasting a coffee to bring it in for you and we don’t have enough information around how it was dried, then we don’t know if we are going to give you a coffee that’s just as vibrant as we first tasted it. Dead coffees taste like wood and cardboard. All the fruit acids, all the sweet flavours fade and you’re left with a bunch of cellulose that somehow has to perform as coffee.

Up against the industrial revolution

If you ever want to take a look around the internet for how the coffee market is doing at any given point, you’ll likely get steered toward market forces and yields and metrics that are only to do with production quantity.

There’s been a huge uptick of drying coffee on patios and figuring out ways to produce more especially in the 1960s up until today.

That focus on yields and productivity inevitably meant that with a traditional market, the price went down (and stayed that way) due to a lack of demand against supply.

It wasn’t always this way

There’s a handbook excerpt that Jason Galvis (who runs the lab at Azahar, the Exporter we work with in Colombia) gave me a few years ago. In it, the Coffee Federation’s education arm had written all this detail around how to dry coffee. This was in the 1930s.

I honestly couldn’t believe how detailed and Quality focused the guide was, carefully pre-drying the coffee to get rid of initial water volume (measuring in specific wooden boxes to gauge when a certain percentage was gone from the seeds). Then the coffee gets moved to raised beds with an awning and completely open sides for the second stage. Finally, the coffee is moved into a drying house for the final, gentle drying before it gets packed up and rested before milling.

Fast forward to today – It’s clear that we didn’t go in the right direction. There are, however, a few people that are drying coffee in this slower, more quality focused way. It’s our prerogative to roll with those folks – I mean it only makes sense. We’re small and focused on quality, so of course, that would extend to the growers we buy from. The idea is small working with small – and a situation where we can all make a sustainable business. Um, and of course, incredible coffee <3

Sometimes we have to look back to look forward. I’ll leave you with that. If you want to pick up the conversation or if there’s something you’d like us to elaborate on in the next letter, let me know – Until next time.