Finding symbiosis: A chat about growing soil for coffee with Raul Perez

Earlier this month, I hopped on a zoom call with our friend Raul Perez, who manages and runs Finca La Soledad as well as El Llano (where both coffees for the June subscription box were grown) along with his dad Henio Perez and little brother Jose in Acatenango, Guatemala. We had a candid discussion about strategic plans for both farms and a whole lot about dirt. Here’s a portion of that conversation.

(edited for brevity)

Raul: I don’t want the process to overcome or overpower the flavours of the variety, or of my farm characteristic. Yes, I want a little bit more fruit probably or a different type of acidity, and that’s the one that I want to encase. But I don’t want the other process to overwhelm the flavours. My girlfriend buys coffee and she exports, she has a lot of offers from one farm or different farms. Sometimes there are 15, 16 coffees, and at number six I’m done with this coffee because all the flavours are the same. It’s the same fermentative flavour that is overpowering the rest. It can be very complicated. If you see the wine industry, they think that they lost some identity right now. Everybody is doing the same, because all of them have the same yeast, or coming from the same labs, and they have the same profile of flavour at the end.

Laura: Yeah, that’s a totally different world that I don’t necessarily know too much about [traditional vs natural wine making]. Going and buying a specific type of yeast and inoculating a tank of coffee with that. You have to believe in natural yeasts that are around the environment. Have you ever thought about the relationship that soil health has to that whole dynamic?

Raul: If you asked me that question maybe a year and a half, three years ago, I will say I don’t know much about it. I still don’t know anything about it, but now the way I’m seeing it, the research that is done by a lot of people, not just in coffee, but in other agriculture products. The soil is the key. The flavours, the nutrition, is coming just from the soil. Not from anything else. I actually saw a lecture. I think it was done in Europe. That Caturra coffee, that one that was made in Europe. It’s a woman that talks about the wines and the terroir of the wine, and how it’s related now to the biology of the soil and how we have been losing that in the way we have been farming.

Isabelle Legeron | Lessons From The ‘Natural Wine’ Movement on the Re:co Symposium YouTube Channel if you’re interested in digging in.]

Laura: I’m so into this topic right now, because it has to do with everything we grow, coffee included. I’m sure we’ve all tasted coffees that look like they’re going to be great. Then we realize through tasting them that the nutrients aren’t there even though the cherries are red.

Raul: We saw it when we were hit by leaf rust at the beginning. It was branches of cherries and they started to get red and then super red and purple. We harvest like we normally do. We were picking the same way as any other year. The skin is red. It was purple, if you want. But the bean inside was not fully developed. We didn’t have enough nutrients inside the bean to make it a more dense bean. Nutrients at the end of the day, they’re flavours. Aromas or magic with the coffee. That’s what we are losing, but we never measured that. The coffee in the 1980s, farming was a little bit different.

When we are facing with this problem in the whole region of Guatemala, we talk about more specifics about the farm because we have been losing productivity before leaf rust. From around the year, 2000, 2002, our productivity started to go down every year. We were applying a little bit more or fertilizers or covering shade trees, doing all of the things, and the impact on the productivity was almost none.

Instead of making more coffee we were making less coffee. It’s more expensive because you are having more inputs into the coffee. Then of course we have the storms. 2004, 2007, the year 2010. Where we have 4,000 millimetres of rain. In 2000, that was a lot of rain and we didn’t initially see the effect on the soil. Now we can see that we lost top soil, for sure. The nutrients inside the soil changed and we didn’t realize it. We haven’t been trying to fix the soil. We’re just put in more inputs and thinking that’s going to be the solution to increase our productivity. But at the end, it’s not working that way.

That’s one of the reasons why I started researching, because it’s not working. It hasn’t been working in the last 10 years. I have been working with my father more closely, and we have done many things. Different ways of pruning and planting. Distance and the varieties. But at the end of the day, the productivity is that the harvest is the test. And we haven’t reached the numbers. Now we have more land and less coffee. Basically. We have more land that we own, and we have less coffee than when my father was owning half of the land. It doesn’t make sense. That’s one of the reasons I started to see that we have a bigger problem that we haven’t been addressing. It turns out that the problem is the soil. It’s the relationship in the soil that is not good anymore. Now, the question is how to fix it. That’s another three hour lecture.

Laura: Yeah, that’s a whole project. That’s kind of like the idea of feeding your microbiome.

Raul: It’s exactly the same. This is the way they are selling this idea. It’s like having food as medicine. Basically it’s that. I know that they have been focusing on a lot of the things, like the beef. How it’s raised and some of the veggies, how they are raised as well. They have been talking about all the products, like avocados, stone fruits. They relate a little bit more to my product. The coffee or the avocado that we have.

Raul: Coffee is more like perennials. They call it more like perennials instead veggies that are in one season.

Laura: Yeah totally.

Raul: These perennial systems are very different from the other ones. We address the perennials in a very different way. It’s a long process.

Laura: That’s super interesting. Of course coffee is a perennial. You can go five, 10 years, some people go more without stumping. Whatever protocol you want to follow. It’s totally true. Fertilizer companies treat it as though it’s a carrot, but it’s not a freaking carrot.

Raul: That has been changing my mind, but still I will say that I am overwhelmed with all this information, new information. Sometimes some things will click with coffee, some others I’m hesitated about. The biggest issue is that I have to fight these ideas with the rest of my family. They don’t believe it still, fully.

Laura: Not an easy feat.

Raul: It’s very complicated, because it’s basically to change the way we were taught from the school, from college. All of these areas, how to produce any agricultural product. A way to solve our problem is “All you have to do is pay”. You have flies? These are the products that will kill the flies.” Instead of asking the questions of why we have flies?

Laura: Yeah, asking instead: What don’t I have that is a natural predator, that can take care of it?

Raul: We [farmers] don’t think that way because it takes a long time to understand. It takes a long time to fight it as well. I get it because, if you ask me, I will try to turn part of the farm in this concept, but I know I can’t because we don’t have the resources and because I am very sure that we’ll fail because we don’t know what’s going to happen. I don’t want to risk a lot of land and kill this project because it will not have the results that we want. We are very sure that we’re going to be making mistakes. We want to just do it with a little bit of land right now.

Laura: That’s totally fair.

Raul: Yeah.

Raul: I’m going to be trying a few little plots this year, to experiment a little bit with this because there are also different ways of adopting these concepts. The concept is really big, so if you go to this doctor, he will say one thing, if you go to this other PhD guy, he will say another thing. If you go to another farmer, he will say a different thing because everybody has a very different opinion about how we should be treating this. I’m trying to listen from the guys who are from the far left, the far, right, the guys in the middle. And try to make a mixture of all the ideas and see which ones I can apply and go in that direction. We can not stop using fertilizers just to call it to zero.

Laura: What are you going to do first?

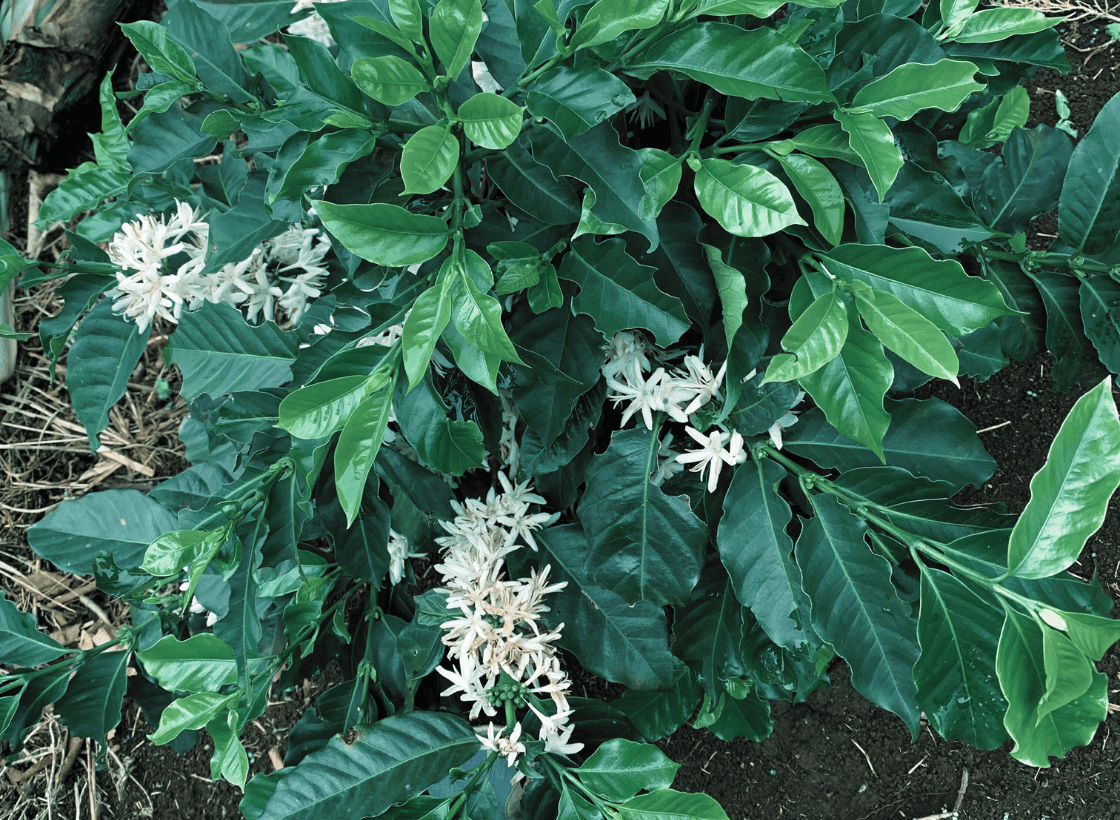

Raul: We’re going to be planting in a couple of weeks, the new section of Anacafé 14. We’re going to start by doing mycorrhizal fungi to the nursery. Also, we’re going to be combining grasses, ornamentation, to have a cover crop all year round. We’re going to be using a little bit of seaweed, some compost. Right now we’re developing the compost and we want to do a piece with the compost, like composting. Just a little bit of information about how this separates the perennials with no perineal. Perennials want more fungi on the soil, so the soil has to have different types of fungi.

Our idea right now, we understand that coffee is a perennial that comes from a forest, so we were trying to emulate that soil from the forest. We need to increase the amount of fungi that we’re going to have. Our compost is going to be focusing on fungi production more than bacteria. That’s why worm compost could be a little bit tricky, because worm compost is more bacterial. That’s one of the reasons, perhaps, why it doesn’t show big effects on coffee. You use it on veggies because it’s more suitable for veggies. Understanding those things, I think are the first steps to identify what we need to do. We’re going to be applying a mycorrhizal fungi. We’re going to be applying humic acids to the soil. Seaweed, also, has part of the food for the microbes. Right now we’re not going to feed the plants. We’re going to feed the soil, not the plants.

Laura: This is cool. I’m so excited to see how it goes.

Raul: In theory, this will help the quality of the coffee as well, because it will have more dense nutrients inside the bean. It will be a better coffee.

Laura: I was thinking about this the other day. It’s like when we take a pharmaceutical approach. This is the problem, okay here is the solution for that specific problem. But you don’t know what you don’t know, and there could be other bio mechanisms or other things that are happening along with it that you might not know about. But the soil knows. The plants know. The hope is that it’ll do what it’s supposed to do.

Laura: I think you can’t really argue with eating vegetables. It’s good for you.

Raul: That’s another thing. We’re going to start planting our own food as well. The farm.

Laura: Nice. That’s awesome. What are you going to plant?

Raul: Tomatoes, potatoes, carrots, beats, cucumbers. I don’t know, onions, spring onions. Whatever we can plant and produce, we can try to do it.

Laura: Beans are probably nice. I don’t know.

Raul: They’re beans! so of course. Black beans, corn. We’re going to be planting some corn as well.

Raul: Our approach, the way we manage our farms, we never like to be fully chemical. We have worm compost. We do a lot of shade. We keep a lot of grass. We haven’t used pesticides since 2004, for example. Even though we have grass like this tall right now. It’s because we don’t have enough people to cut it and it’s raining a lot. We understand that this is part of it. We are covering the soils. We’re retaining the soil. We’re not losing a lot of soil with these heavy rains that we have been having in the last four weeks. We’re planting more shade trees, different types. That has always been our approach.

We understand that something is happening. Even though we are planting Anacafé 14 or H1 or others that are resistant, we are not reaching their potential on productivity. That’s for a reason. I mean, you place a variety, you see an improvement, but you know that you’re not reaching the potential. Those are the questions that we were asking all the time. “Why are we not reaching the potential? We have really good conditions over there [at El Llano].” At the end of the day, we are seeing that it’s mostly because of the soil, and we need to improve that soil. It’s going to be a long process, but we are starting a little.

Laura: This is a really weird question, but I’m thinking about how you have really tall grass. Is there a goat that you could get to work for the day and it’ll mow the cover crops for you?

Raul: There’s a type of goat that they will be eating the grass. For sure. That’s another thing. With these approaches, different people that we have been studying, they call it stacking. I don’t remember the word, but the idea is to have chickens because they will spread fertilizer to kill the insects. You have goats or pigs or cows in the same farm. You’re producing more things, but coffee at the same time. I’m not sure if we’re going to have cows because of the size.

Laura: That’s a lot of work.

Raul: A lot of work, but we’re thinking on doing these sheep or goats.

Raul: But yeah, our idea is to go through four hybrids, actually we’re testing all the hybrids. We’ll see the results from that. And yeah, we think that’s kind of our future in coffee.

Laura: Yeah. For sure. I think it’s a nice approach to take… I kind of see hybrids as being able to take a breath and say like, “Okay, I have the hybrid. It’s not going to have leaf rust probably. So this gives me a chance to work on the soil now.” And I think that’s a nice long-term approach. I didn’t really tell you how I thought about heavy processing. I think I can understand why it’s so exciting to people, but I think it’s a little bit of a distraction and kind of short-sighted seeing as there’s a much bigger problem to solve, I guess. Yeah. So it’s nice, it’s good. Do it. It’s great as a short term thing to build in value on a farm. But how’s your soil doing? What varieties are you planting? All of these other things that are not from year to year that are more multi-year projects.

Raul: Yeah. And sometimes, I don’t know, coffee can be very difficult… Coffee producing specifically as a farmer could be a little bit difficult, seeing a different approach. It doesn’t matter which approach at the end of the day, because at some point the most difficult part for a lot of farmers is to sell their own products. And I’m telling you this, because let’s say like eight to 10 years ago, people were saying like, oh, you need to have Geisha in the farm. You need to have Geisha because Geishas are expensive because you can sell it for a lot of money. And that’s how you’re going to save your farm.” And I know farmers from Acatenango that they are producing a few bags of Geisha and they were not able to sell it. They have Geisha from last year. Still, without selling it.

Yeah. This guy is producing one hundred bags of Geisha and he sells 20. And the rest are still sitting in the warehouse. So for me, it’s like if you have the market, yes, you can do a few things. But if you don’t have it, you have to be very careful of what you are planting or your expectations. So it comes to not just education, but people are just like whatever variety that you are producing or whatever thing that people are producing, they have to be aware that coffee is not, it doesn’t have a single solution. It could be the soil, could be the variety. It could be the processing and it could be how you sell it, who you’re selling that coffee to.

Laura: Oh definitely.

Raul: It’s a multilayer solution. It’s not just one. The problem is that we always focus on just one because we want to see the results super fast, and coffee it’s not fast.

Laura: It’s the furthest thing from fast.

Raul: Has nothing to do with fast. I mean, even, you roast the coffee you have to wait at least 24 hours to cup it. So it’s telling you that you need to take some time to wait and see what’s going on. For us as farmers takes five years, seven years to have solutions or answers.

Laura: Oh totally. I mean, we have a hard enough time trying to keep customers in the loop about, “Okay we tasted and contracted a coffee. Okay, now it’s on ocean freight. Okay, 60 days later, oh, it’s almost here. Okay, unload it. Okay, it’s finally here.” And meanwhile, I end up having very long conversations with customers on Instagram DMs, because they’re like, “I hope you put this coffee in stock soon.” And I’m like, “Oh, it doesn’t work like that.” I have to explain that it’s a harvest cycle and it’s done for the year and it’ll come back and it’s not us just picking coffees off the shelf in a warehouse somewhere. It’s a little bit different than that. They get it and appreciate knowing, which is awesome.

So there’s that as well. I think there are a few issues in coffee that I do think are solvable. And I think that you and the whole family are a testament to that because of how you started to sell directly to roasters and what that did because it’s a small business. So yeah, I think there’s awesome potential in that for people who are small farmers and want to have more autonomy and control over their business, and how that brings more stability. Yeah. I think it’s super important.

Raul: No, it’s very important. And I think the keyword of all of this is stability. Yeah. And for me, I always say that this network of buyers that we have, plus a couple of other things, the basic, the most important thing is stability. We know that next year everybody’s going to be there, they’re just waiting for us to make good quality, clean, and yeah, nice coffees.

Laura: Yeah

Raul: So for us, we don’t have to worry about that anymore. To be honest.

Laura: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, that’s awesome. For some people that’s all they’re doing [trying to sell] but because they’re taking their time doing all that they don’t have time to think ahead to treating the farm as a perennial farm, for example.

Raul: That’s the approach. That’s the new approach.

Laura: Yeah. That’s so cool.